[Note: As this is taken from an archived site, some links and videos below may not be working.]

How Jews purloined the bloodbath blood libel

Almost everything in

this post I've learnt from the following three papers listed below.

This is only a brief overview of the Pharaoh's Bloodbath, and I

recommend reading the three cited papers for a fuller view.

Infanticide in Passover

Iconography (1993) by David J. Malkiel. here

Pharaoh's Bloodbath (2009) by Ephraim Shoham-Steiner. here

Sacrifice and Redemption in the Hamburg Miscellany (2012)

by Zsofia Buda. pdf

thru here

This is a depiction of the Roman Emperor Constantine sick with leprosy,

with Saint Peter and Saint Paul who, according to legend, appeared

before Constantine in a dream. It is part of a fresco dated to 1246, in

the Chapel of Saint Sylvester in

Santi

Quattro Coronati, Rome. Photo

source.

The Legenda

Sancti Silvestri (or Actus

Silvestri) which dates between 480—490, is a romanticised (false)

account of Constantine's conversion to Christianity. The Legenda claims

that Constantine had been advised by pagan priests in Rome that the only

cure for his leprosy would be to bathe in the blood of slaughtered

children, but St. Peter and St. Paul appeared to Constantine in a dream

and appealed to him to substitute children's blood for the water of

baptism. The Legenda claims Constantine

submitted to the Saint's request, and was soon baptised by Pope

Sylvester c.312. In reality, Constantine was baptised on his

death-bed in 337 by Bishop

Eusebius.

An

awfully similar legend to Constantine and his prescribed bloodbath,

later appeared in Jewish rabbinism, which, initially at least, also had

a similar happy ending; the bath of children's blood was avoided. But in

later Jewish tradition, the happy ending was dropped and the bloodbath

became a "historical" event.

"For the rabbis,

the Bible is simply an immense metaphor."

— Talmud:

A film by Pierre-Henry Salfati

Rabbinical Jews do not

interpret Exodus 2:23-25 literally.

Although it states "the king of Egypt died", they believed that

it meant 'the king of Egypt caught leprosy, and was advised by his

physicians/necromancers to bathe daily in the blood of 300 Jewish

babies, but God cured him following pleas from the Hebrews.' But as I've

learnt, this story was pilfered from the legend of Constantine's

conversion, and in the Middle Ages it was amended by Ashkenazi Jews into

a more horrific version, where the Pharaoh actually did bathe daily in

the blood of Jewish babies, and it's this version is propagated by

Hasidic Jews to this

day.

The story of the

Pharaoh's bloodbath originates in the Shemot Raba (sometimes Rabbah),

a Midrash, a Rabbinical commentary of the Book of Exodus,

which The Jewish Encyclopedia (Vol

8, 1904, p.562) suggests dates from the 11th or 12th century,

although it also concedes parts of it might be considerably older c.7th

century. The Shemot Raba states of Exodus 2:23-25:

"The king of Egypt

died—he contracted leprosy, and a leper is considered dead ... And the

Children of Yisrael moaned—why did they moan? Because the necromancers

of Egypt told Pharaoh that he had no cure other than to slaughter the

infants of the Children of Yisrael, 150 by evening and 150 by morning,

and to bathe in their blood twice a day. And God remembered His

covenant—our Rabbis teach that a miracle occurred for them, and he was

cured of his leprosy." (Shemos Rabbah 1:35).

As you can see, in the Shemos

Rabbah the bloodbath was avoided, as God cured the Pharaoh, but that

was to change.

The

immensely influential French Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhak, known as Rashi (1040—1105),

whose commentary on the Talmud, has been included in

every single edition of the Talmud for

the last several hundreds years, wrote of Exodus 2:23

in his commentary of

the Tanakh (Jewish Bible):

"The king of

Egypt died—he became a leper [who

is deemed as one dead],

and he used to slaughter Israelite children and bathe in their blood

[as a cure for his disease]."

The Targum

Pseudo-Jonathan,

an Aramaic and paraphrased translation of the Bible, which

might originate from the seventh or eighth century, possibly earlier,

possibly later (12th century). The original no longer exists, and the

only existing "copy" is from the 16th century. It states in Exodus 2:23:

"After a long

time the King of Egypt was afflicted with leprosy, and he ordered

the first-born of the Israelites to be killed so that he might bathe

in their blood."

The Midrash

ha-Gadol (13th century, Yemen) states:

"Pharaoh had

three advisers. When he contracted leprosy, he asked the physicians

what would heal him. Balaam advised him to slaughter the Jews and

bathe in their blood in order to be healed. Job was silent, implying

agreement. Jethro heard and fled. He that advised was killed, he

that was silent was tormented, and he that fled merited the addition

of a letter to his name: it had be Jether [Exodus 4.18], and became

Jethro."

Sefer ha-Yashar (c.13th

century) states:

"When God struck

Pharaoh with disease, he asked his scholars and magicians to heal

him. They said that he would be cured if he put the blood of little

children on the diseased area. Pharaoh accepted this advice, and

sent his attendants to Goshen, to the Israelites, to take their

little children. The attendants went off, and took the Isrelites'

children from their mothers' bosoms by force. They brought them to

Pharaoh each day, one at a time, and the physicians slaughtered them

and applied the blood to the diseased area. They did this every day,

until the number of children slaughtered by Pharaoh reached 375. God

did not heed the Egyptian king's physicians, and the disease grew

stronger. Pharaoh suffered this illness ten years."

I will just mention that many people have claimed over the centuries

that kings of Egypt did bathe in human blood in an attempt to cure

leprosy, and cite as a source the Roman chronicler Pliny the Elder (23AD

- 79AD). Here's precisely what he wrote:

"Aegypti

peculiare hoc malum et, cum in reges incidisset, populis

funebre, quippe in balineis solia temporabantur humano sanguine

ad medicinam eam. et hic quidem morbus celeriter in Italia

restinctus est, sicut et ille, quem gemursam appellavere prisci

inter digitos pedum nascentem, etiam nomine oblitterato."

Natural History,

Volume 26, Chapter 5, Verse

8

"This disease was

originally peculiar to Egypt. Whenever it attacked the kings of that

country, it was attended with peculiarly fatal effects to the

people, it being the practice to temper their sitting-baths with

human blood, for the treatment of the disease." (trans.

by J. Bostock)

In his 2009 paper Pharaoh's

Bloodbath Medieval European Jewish Thoughts about Leprosy Disease and

Blood Therapymore, Dr. Ephraim Shoham-Steiner of Ben Gurion

University of the Nege argues that Jews in the Late Antiquity period,

hijacked the leprous Constantine bloodbath and redemption legend from

the Legenda Sancti Silvestri, and remodelled it in

the Shemot Raba around the Pharaoh, and

the renewed concern the God showed for the Hebrews in Exodus 2:23-25 (which

would lead to their deliverance from Egypt). But, Shoham-Steiner adds:

"by the twelfth and

thirteenth centuries, the Jewish midrashic story supplied by Shemot Raba

no longer served its purpose. Jewish-Christian relations had undergone a

change for the worse. In the aftermath of the 1096 riots and the acts of

infanticide and martyrdom, miraculous deliverance no longer satisfied

Ashkenazi Jews. They wanted revenge for the martyred Jews of the

crusades and other anti-Jewish riots and libels.

The

eschatological ideology of an avenging God that would come and

"settle the score" with Gentiles was by that time not an abstract

notion related to eschaton but a pressing issue. In the minds of

many Jews of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the blood of

innocent Jews functioned as a tool to invoke divine wrath in the

final judgment and the subsequent violent retribution towards the

Gentiles who spilled innocent Jewish blood. According to this view,

Pharaoh could not have been healed, innocent Jewish blood had to

be and was spilt, and this blood was an important component in

the process of deliverance; it was to be present before the Lord on

the day of final judgment.

(emphasis in original)

A

Modern

Haggadah based on the earliest known illustrated

Ashkenazi Haggadah

The Haggadah is

a brief overview of the Exodus story, that Jews are supposed to read at

their Passover dinners each and every year. In the 14th

century, Illuminated Haggadah appeared, which are essentially

illustrated Haggadah. The earliest known Ashkenazi Illuminated Haggadah,

is the so-called Bird's Head Haggadah (c.1300), where the illustrated

figures of Jews have bird's faces, and the non-Jews (Pharaoh, Egyptians,

angels, etc.) are depicted with no faces at all. The reason for this was

to circumvent the rabbinical ban on Jewish image making, reminiscent of

the prohibition originating from the Hadith of Sunni Islam, which

forbids all images of not just Mohammad, but all humans, animals, and

angels etc.

Shoham-Steiner

details how the

amending of the hijacked bloodbath legend, from its original

happy-ending (no bloodbaths) to version where the malevolent Pharaoh

regularly bathed in the blood of Jewish youths, is evident in the

Illustrated Haggadah of the 14th and 15th century.

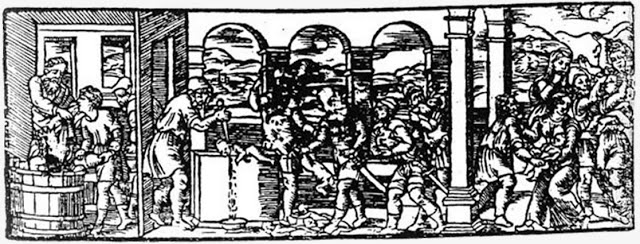

Illustrations

on "folio 15V" (full

page here)

from the Bird's Head Haggadah

Shoham-Steiner

describes how the image on the right "the

binding of Isaac" on the Bird's Head Haggadah (c.1300), was replaced

on later 15th century Haggadahs with images of the Pharaoh sitting in a

bloodbath, and of Egyptians slaughtering infants for his bath.

Shoham-Steniner suggests that Ashkenazi Jews were "too intimidated

to present an image or a scene that might have implicated them as those

who slaughter rather than those who are slain." He

writes:

"The difference

is significant, for aside from its polemical meaning, the Binding of

Isaac signifies, probably more than any other scene from Genesis or

the entire Hebrew Bible, the concept of the merit of the Patriarchs.

It represents the ultimate sacrifice on the part of the two

Patriarchs involved. In late antiquity, as well as in the Middle

Ages, Jews saw the Binding of Isaac as the constituent core of the

Patriarchs' merit, the act that resonates far beyond the Patriarchs

to their immediate kin—the Children of Israel—enabling Jews to make

the most of this extreme gesture of ultimate faith in God.

Interestingly, this is the exact theme that Ashkenazi Jews had

altered when they deviated from the Shemot Raba tradition. In their

minds, the blood of innocent children designed to heal Pharaoh's

leprosy was spilt and that blood symbolically harbored the

redemptive qualities they saw in their own blood spilt during riots

and libels."

Shoham-Steiner cites

"the Nuremberg Haggadah" as an example of how the Binding of Isaac was

replaced by the Pharaoh's Bloodbath. There is the First Nuremberg

Haggadah (c.1449) and the Second Nuremberg Haggadah

(1450-1500), the First is

not available online, but the Second is

viewable through this

link (you'll

need DjVu), and a full description and translation is viewable on this pdf from

the National Library of Israel. Below are images from page

14 of

the Second

Nuremberg Haggadah,

and the captions are quoted from the aforementioned description

available from the National Library of Israel.

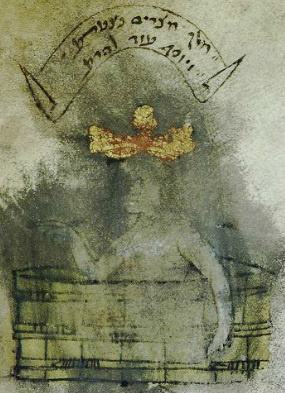

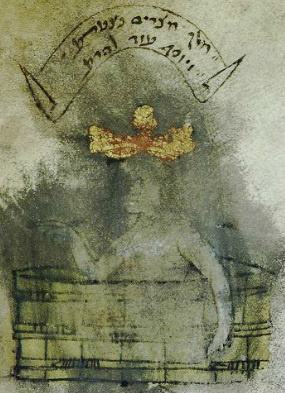

|

"In the outer margin, crowned Pharaoh is sitting naked in a bathtub,

possibly full with blood."

"Inscribed above Pharaoh:

עוד להרע." נצטרע/ ויוס מצרי "מל

(The king of Egypt became leprous, and he became even more evil)" |

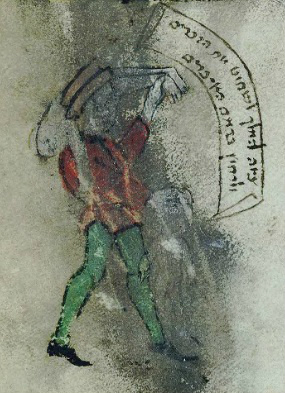

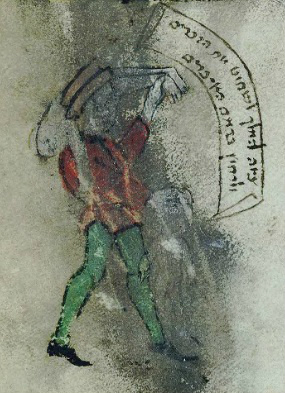

|

|

"Below, an Egyptian is carrying

the corpses of children (badly damaged)"

"Above the Egyptian is

inscribed:

האיברי בדמ " / ולרחו לשחוט את

הזכרי "ציוה המל

(The king ordered the males to

be slaughtered, and his limbs to be washed in their blood)"

|

Below are other images

of the Pharaoh's bloodbath mostly from Haggadahs

created between 1427 and

1690, but also one from a Hebrew prayer book:

This images and the one

immediately above it, are from the same page

(folio 13) of the Yahuda Haggadah (c.1450).

The top image depicts the Pharaoh sitting in his bloodbath, the other

shows a man swinging a cleaver at a infant, whilst another man has two

infants impaled on a spear slung over his shoulder, and an infant

grasped in left hand. A corpse of an infant lays on the floor between

the two men.

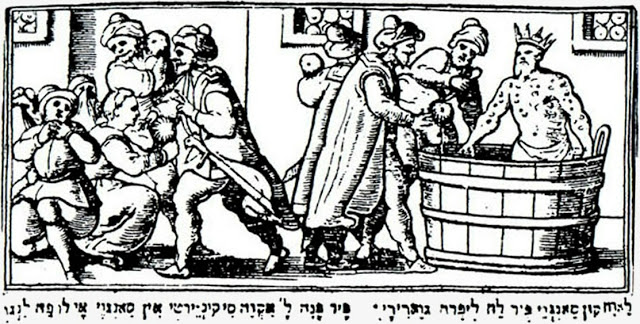

The two images

immediately above are from a Haggadah found in the so-called Hamburg

Miscellany a collection of Hebrew documents (c. 1427").

Once again the Pharaoh is depicted in his bloodbath, and beneath, two of

lackeys are shown with three Jewish children and a bucket to collect

their blood to fill the Pharaoh's bath.

This image of the

Pharaoh in his bloodbath

Mantua Haggadah, 1560

Second Prague Haggadah, c.1580

Venice Haggadah, 1609

The four images above are reproduced from Ariel Toaff's

Blood

Passover

------------------------------

"When a Jew, in America or in South Africa, talks to

his Jewish companions about 'our' government, he means the

government of Israel."

- David Ben-Gurion, Israeli Prime Minister

Viva Palestina!

Latest Additions

- in English

What is this Jewish

carnage

really about? - The background to

atrocities

Videos on Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam and Blacks and Jews

How Jewish Films and Television Promotes bias Against

Muslims

Judaism is Nobody's

Friend

Judaism is the Jews' strategy to

dominate non-Jews.

Jewish War Against

Lebanon!

Islam and Revolution

By Ahmed Rami

Hasbara -

The Jewish manual

for media deceptions

Celebrities bowing to their Jewish masters

Elie Wiesel - A Prominent False Witness

By Robert Faurisson

The Gaza atrocity 2008-2009

Iraq - war and occupation

Jewish War On

Syria!

CNN's Jewish version of "diversity"

- Lists the main Jewish agents

Hezbollah the Beautiful

Americans, where is your own Hezbollah?

Black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan's Epic Speech in Madison Square

Garden, New York

- A must see!

- A must see!

"War on Terror" -

on Israel's behalf!

World Jewish Congress: Billionaires, Oligarchs, Global Influencers for Israel

Interview with anti-Zionist veteran Ahmed Rami of Radio Islam

- On ISIS, "Neo-Nazis", Syria, Judaism, Islam, Russia...

Britain under Jewish

occupation!

Jewish World Power

West Europe

East Europe

Americas

Asia

Middle East

Africa

U.N.

E.U.

The Internet and

Israeli-Jewish infiltration/manipulations

Books

- Important collection of titles

The Judaization of

China

Israel: Jewish Supremacy in Action

- By David Duke

The Power of Jews in France

Jew Goldstone appointed by UN to investigate War Crimes in Gaza

The best book on Jewish Power

The Israel Lobby

- From the book

Jews and Crime - The archive

Sayanim - Israel's and Mossad's Jewish helpers abroad

Listen to Louis Farrakhan's Speech

- A must hear!

The Israeli Nuclear Threat

The "Six

Million" Myth

"Jewish History"

- a bookreview

Putin and the

Jews of Russia

Israel's attack on US warship USS Liberty

- Massacre in the Mediterranean

Jewish "Religion" - What is

it?

Medias

in the hands of racists

Strauss-Kahn - IMF chief and member of Israel lobby group

Stop Jewish Apartheid!

The Jews behind Islamophobia

Israel controls U.S. Presidents

Biden, Trump, Obama, Bush, Clinton...

The Victories of Revisionism

By Professor Robert Faurisson

The Jewish hand behind Internet

The Jews behind Google, Facebook, Wikipedia,

Yahoo!, MySpace, eBay...

"Jews, who want to be decent human beings, have to renounce being Jewish"

Jewish War Against Iran

Jewish Manipulation of World Leaders

Al Jazeera English under

Jewish infiltration

Garaudy's "The Founding

Myths

of Israeli Politics"

Jewish hate against Christians

By Prof. Israel Shahak

Introduction to Revisionist

Thought

- By Ernst Zündel

Karl Marx: The Jewish Question

Reel Bad Arabs

- Revealing the racist Jewish Hollywood propaganda

"Anti-Semitism" - What is it?

Videos

- Important collection

- Important collection

The Jews Banished 47 Times in 1000 Years - Why?

Zionist

strategies

- Plotting invasions, formenting civil wars, interreligious strife,

stoking racial hatreds and race war

The International Jew

By Henry Ford

Pravda interviews Ahmed Rami

Shahak's

"Jewish History,

Jewish Religion"

The Jewish plan to destroy the Arab countries

- From the World Zionist Organization

Judaism and Zionism inseparable

Revealing photos of the Jews

Horrors of ISIS Created by Zionist Supremacy

- By David Duke

Racist Jewish Fundamentalism

The Freedom Fighters:

Hezbollah

- Lebanon

Hezbollah

- Lebanon

Nation of Islam

- U.S.A.

Nation of Islam

- U.S.A.

Jewish Influence in America

- Government, Media, Finance...

"Jews" from

Khazaria stealing the land of Palestine

The U.S. cost of supporting Israel

Turkey, Ataturk and

the Jews

The truth about the Talmud

Israel and the Ongoing Holocaust in Congo

Jews DO control the media -

a Jew brags!

- Revealing Jewish article

Abbas - The Traitor

Protocols of Zion

- The whole book!

Encyclopedia of the

Palestine Problem

The

"Holocaust" - 120 Questions and Answers

Quotes

- On Jewish Power / Zionism

Caricatures / Cartoons

Activism!

- Join the Fight!