[Note: As this article is reconstructed from a copy some

content/layout may vary from the original posting.]

Ribbentrop also denied Hitler ordered the Holocaust

Herman Goering denied even knowing about the mass executions of Jews

whilst he was on the stand at the main Nuremberg Trial, stating:

This I maintain, and the reason for this is that these

things were kept secret from me. I might

add that in my opinion not even the Führer knew

the extent of what was going on. This

is also explained by the fact that Himmler kept all

these matters very secret. We were never given figures

or any other details.

But Goering wasn't the only senior

member of the NSDAP who was of the opinion that

Hitler did not order the mass killing of Jews. I've recently obtained a

copy of the

memoirs of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Foreign Minister. He

too was

tried and sentenced to death

by hanging at Nuremberg, but in the last few

weeks of his

life, he wrote his memoirs which were published in

1953 and English in 1954.

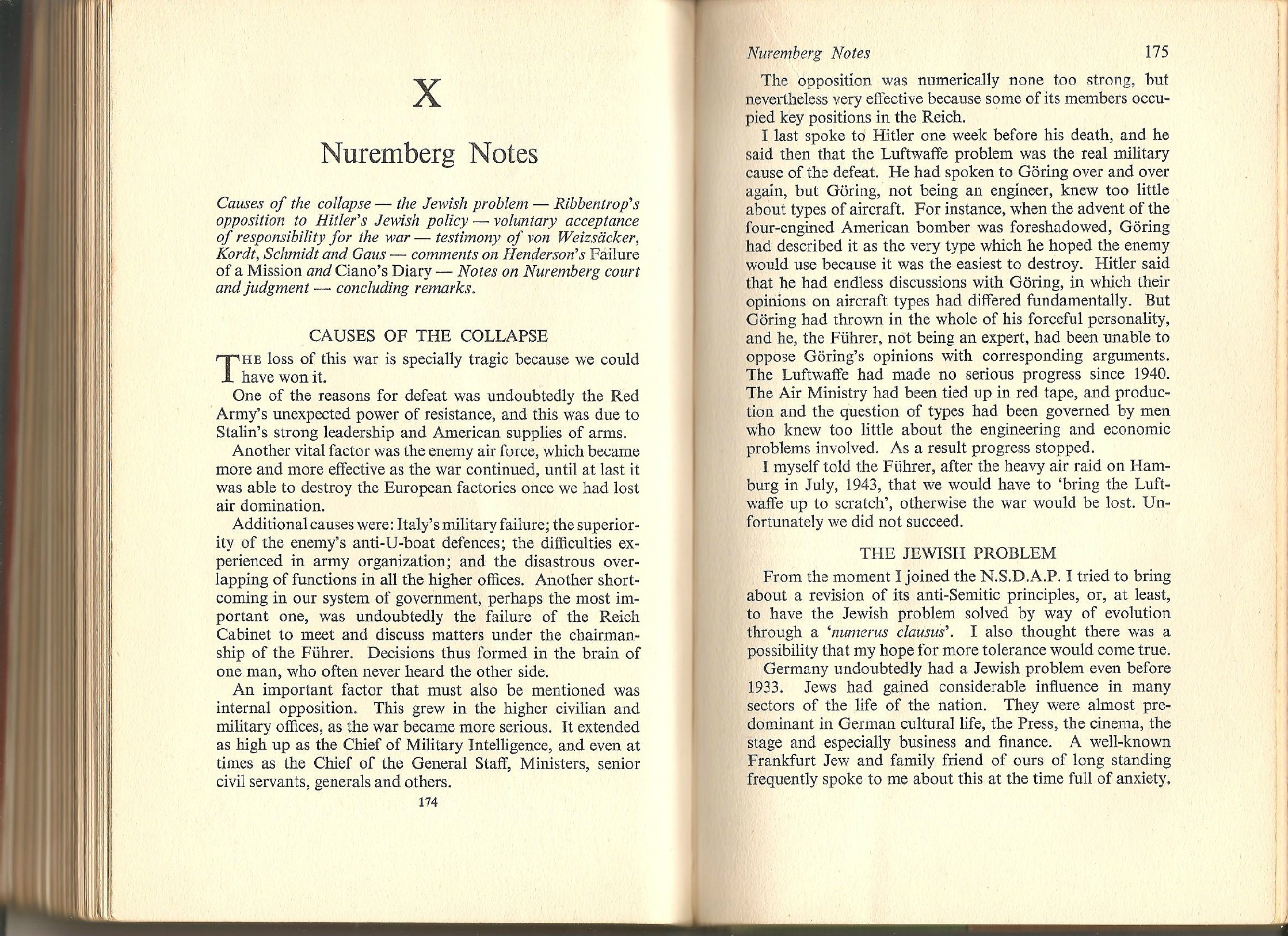

THE JEWISH PROBLEM

From the moment I

joined the N.S.D.A.P. I tried to bring about a revision of its

anti-Semitic principles, or, at least, to have the Jewish

problem solved by way of evolution through a 'numerus clausus'.

I also though there was a possibility that my hope for more

tolerance would come true.

Germany

undoubtedly had a Jewish problem even before 1933. Jews had

gained considerable influence in many sectors of the life of

the nation. They were almost predominant in German cultural

life, the Press, the cinema, the stage and especially

business and finance. A well-known Frankfurt Jew and family

friend of ours of long standing frequently spoke to me about

this at the time full of anxiety. He was worried lest the

conduct of certain German and immigrant Jews should lead to

serious conflict sooner or later.

After the

promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws in September, 1935, I had

a long detailed talk with the Führer about the Jewish

question. It was soon after the conclusion of the Naval

Agreement with Britain; the Führer had great confidence in

me, and I therefore pointed out the repercussions these Laws

would have abroad. His reply seemed to me to indicate that

the new legislation was intended to be the concluding

measure, and that the Jews, while very much restricted in

their scope, would retain an altogether fair chance of

Hitler and of Party headquarters up to 1936, when I left for

London, appeared to be not unfavourable to the emergence of

quite toleration.

When in 1938 I

returned to Berlin as Foreign Minister I found an entirely

new situation. The reaction of world Jewry, especially in

the U.S.A., to the Nuremberg Laws had been strong, and the

result had been the sharpest attacks on National Socialist

Germany, especially in the foreign Press. This in turn had

made the Führer much harder. The vicious circle had begun.

Following the

murder by the Jew Grunspan of Legation Counsellor vom Rath

in our Paris Embassy, the well-known excesses against Jews

occurred in November, 1938. As soon as I heard of them I

went to the Obersalzberg and told Hitler of the serious

effect such illegal anti-Semitic measures were bound to have

on our own German people, and the inevitable political

consequences. Hitler replied in deadly earnest that it was

not always possible to detirmine the course of events as one

liked, and that everything would return to its normal

course. I had the impression that Hitler himself was

surprised by the extent of the reaction.

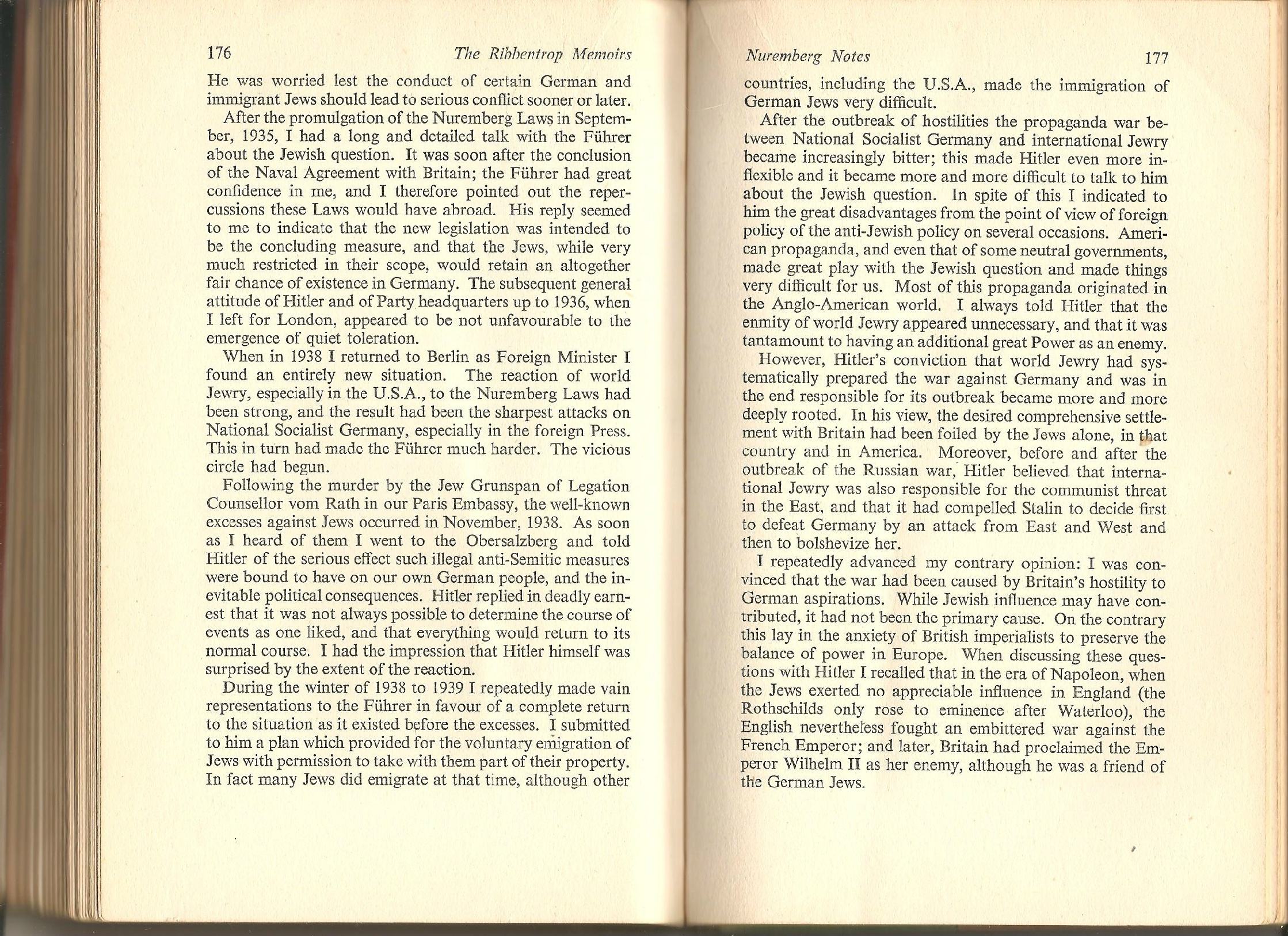

During

the winter of 1938 to 1939 I repeatedly made vain

representations to the Führer in

favour of a complete return to the situation as it existed

before the excesses. I submitted to him a plan which

provided for the voluntary emigration of Jews with

permission to take with them part of their property. In fact

many Jews did emigrate at that time, although other

countries, including the U.S.A., made the immigration of

German Jews very difficult.

After the

outbreak of hostilities the propaganda war between National

Socialist Germany and international Jewry became

increasingly bitter; this made Hitler even more

inflexible and it became more and more difficult to talk to

him about the Jewish question. In spite of this I indicated

to him the great disadvantages from the point of view of

foreign policy of the anti-Jewish policy on several

occasions. American propaganda, and even that of some

netural governments, made great play with the Jewish

question and made things very difficult for us. Most of this

propaganda originated in the Anglo-American world. I

always told Hitler that the enmity of world Jewry appeared

unnecessary, and that it was tantamount to having an

additional great power as an enemy.

However,

Hitler's conviction that world Jewry had systematically

prepared the war against Germany and was in the end

responsible for its outbreak became more and more deeply

rooted. In his view, the desired comprehensive

settlement with Britain had been foiled by the Jews alone,

in that country and in America. Moreover, before and after

the outbreak of the Russian war, Hitler

believed that international Jewry was also responsible for

the communist threat in the East, and that it had compelled

Stalin to decide first to defeat Germany by an attack from

East and West and then to bolshevize her.

I repeatedly

advanced my contary opinion: I was convinced that the war

had been caused by Britain's hostility to German

aspirations. While Jewish influence may have contributed, it

had not been the primary cause. On the contary this lay in

the anxiety of British imperialists to preserve the balance

of power in Europe. When discussing these questions with

Hitler I recalled that in the era of Napoleon, when the Jews

exerted no appreciable influence in England (the Rothschilds

only rose to eminence after Waterloo), the English

nevertheless fought an embittered war against the French

Emperor; and later, Britain had proclaimed the Emperor

Wilhelm II as her enemy, although he was a friend of the

German Jews.

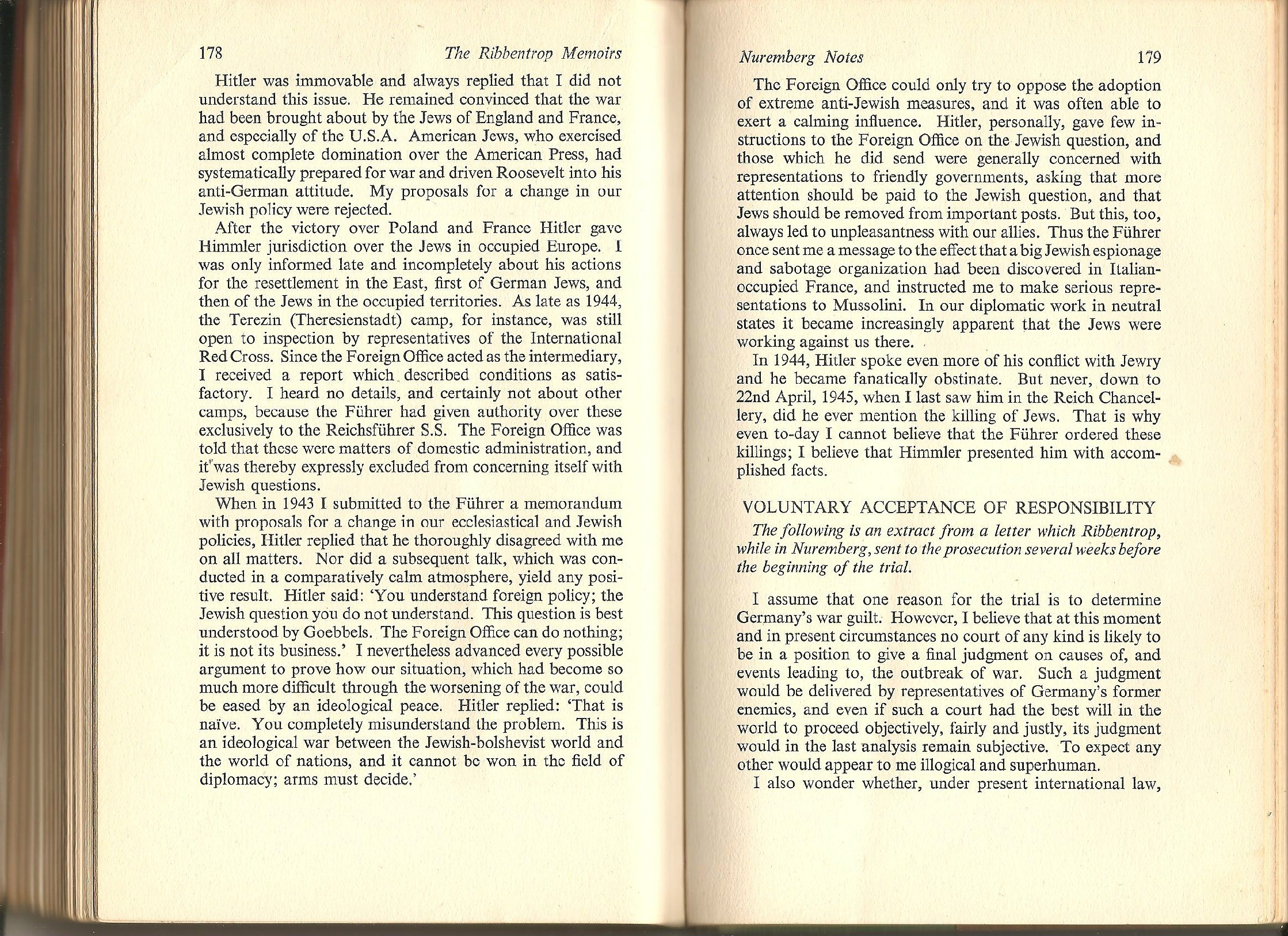

Hitler was

immovable and always replied that I did not understand this

issue. He

remained convinced that the war had been brought about by

the Jews of England and France, and especially of the U.S.A.

American Jews, who exercised almost complete domination over

the American Press, had systematically prepared for war and

driven Roosevelt into his anti-German attitude. My

proposal for a change in our Jewish policy were rejected.

After

the victory over Poland and France Hitler gave Himmler

jurisdiction over the Jews in occupied Europe. I

was only informed late and incompletely about his actions

for the resettlement in the East, first of German Jews, and

then of the Jews in the occupied territories. As

late as 1944, the Terezein (Theresienstadt) camp, for

instance, was still open to inspection by representatives of

the International Red Cross. Since the

Foreign Office acted as the intermediary, I received a

report which described conditions as satisfactory. I heard

no details, and certainly not about other camps, because the

Führer had given authority over these exclusively to the

Reichsführer S.S. (Himmler.) The Foreign Office wastold that

these matters of domestic administration, and it was thereby

expressly excluded from concerning itself with Jewish

questions.

When in 1943 I

submitted to the Führer a memorandum with proposals for a

change in our ecclesiastical and Jewish policies, Hitler

replied that he thoroughly disagreed with me on all matters.

Nor did a subsequent talk, which was conducted in a

comparatively calm atmosphere, yield any positive result.

Hitler said: 'You understand foreign policy; the Jewish

question you do not understand. This question is best

understood by Goebbels. The Foreign Office can do nothing;

it is not its business.' I nevertheless advanced every

possible argument to prove how our situation, which had

become so much more difficult through the worsening of the

war, could be eased by an ideological peace. Hitler

replied: 'That is naïve. This is an

ideological war between the Jewish-bolshevist world and the

world of nations, and it cannot be won in the field of

diplomacy; arms must decide.'

The Foreign

Office could only try to oppose the adoption of extreme

anti-Jewish measures, and it was often able to exert a

claming influence. Hitler, personally, gave few instructions

to the Foreign Office on the Jewish question, and those

which he did send were generally concerned with

representations to friendly governments, asking that more

attention should be paid to the Jewish question, and that

Jews should be removed form important posts. But this, too,

always led to unpleasantness with out allies. Thus the

Führer once sent me a message to the effect that a big

Jewish espionage and sabotage organization had been

discovered in Italian-occupied France, and instructed me to

make serious representations to Mussolini. In

our diplomatic work in neutral states it became increasingly

apparent that the Jews were working against us there.

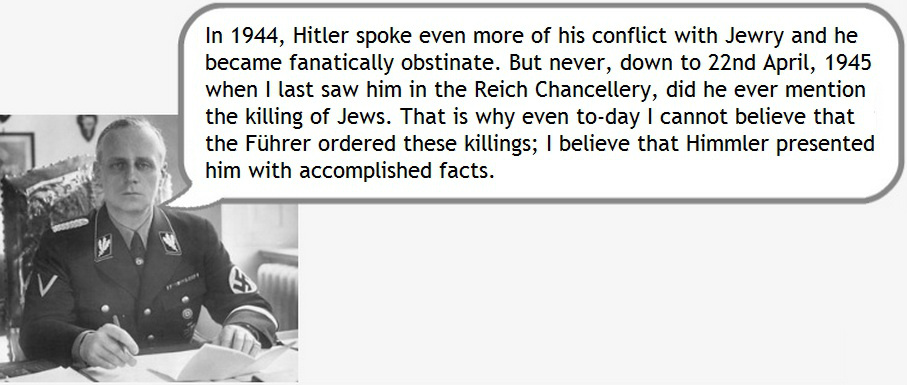

In 1944, Hitler spoke

even more of his conflict with Jewry and

he became fanatically obstinate. But

never, down to 22nd April, 1945 when I last saw him in the

Reich Chancellery, did

he ever mention the killing of Jews. That

is why even

to-day I cannot believe that the Führer ordered these

killings; I

believe that Himmler presented him with accomplished facts.

------------------------------

"When a Jew, in America or in South Africa, talks to

his Jewish companions about 'our' government, he means the

government of Israel."

- David Ben-Gurion, Israeli Prime Minister

Viva Palestina!

Latest Additions

- in English

What is this Jewish

carnage

really about? - The background to

atrocities

Videos on Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam and Blacks and Jews

How Jewish Films and Television Promotes bias Against

Muslims

Judaism is Nobody's

Friend

Judaism is the Jews' strategy to

dominate non-Jews.

Jewish War Against

Lebanon!

Islam and Revolution

By Ahmed Rami

Hasbara -

The Jewish manual

for media deceptions

Celebrities bowing to their Jewish masters

Elie Wiesel - A Prominent False Witness

By Robert Faurisson

The Gaza atrocity 2008-2009

Iraq - war and occupation

Jewish War On

Syria!

CNN's Jewish version of "diversity"

- Lists the main Jewish agents

Hezbollah the Beautiful

Americans, where is your own Hezbollah?

Black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan's Epic Speech in Madison Square

Garden, New York

- A must see!

- A must see!

"War on Terror" -

on Israel's behalf!

World Jewish Congress: Billionaires, Oligarchs, Global Influencers for Israel

Interview with anti-Zionist veteran Ahmed Rami of Radio Islam

- On ISIS, "Neo-Nazis", Syria, Judaism, Islam, Russia...

Britain under Jewish

occupation!

Jewish World Power

West Europe

East Europe

Americas

Asia

Middle East

Africa

U.N.

E.U.

The Internet and

Israeli-Jewish infiltration/manipulations

Books

- Important collection of titles

The Judaization of

China

Israel: Jewish Supremacy in Action

- By David Duke

The Power of Jews in France

Jew Goldstone appointed by UN to investigate War Crimes in Gaza

The best book on Jewish Power

The Israel Lobby

- From the book

Jews and Crime - The archive

Sayanim - Israel's and Mossad's Jewish helpers abroad

Listen to Louis Farrakhan's Speech

- A must hear!

The Israeli Nuclear Threat

The "Six

Million" Myth

"Jewish History"

- a bookreview

Putin and the

Jews of Russia

Israel's attack on US warship USS Liberty

- Massacre in the Mediterranean

Jewish "Religion" - What is

it?

Medias

in the hands of racists

Strauss-Kahn - IMF chief and member of Israel lobby group

Stop Jewish Apartheid!

The Jews behind Islamophobia

Israel controls U.S. Presidents

Biden, Trump, Obama, Bush, Clinton...

The Victories of Revisionism

By Professor Robert Faurisson

The Jewish hand behind Internet

The Jews behind Google, Facebook, Wikipedia,

Yahoo!, MySpace, eBay...

"Jews, who want to be decent human beings, have to renounce being Jewish"

Jewish War Against Iran

Jewish Manipulation of World Leaders

Al Jazeera English under

Jewish infiltration

Garaudy's "The Founding

Myths

of Israeli Politics"

Jewish hate against Christians

By Prof. Israel Shahak

Introduction to Revisionist

Thought

- By Ernst Zündel

Karl Marx: The Jewish Question

Reel Bad Arabs

- Revealing the racist Jewish Hollywood propaganda

"Anti-Semitism" - What is it?

Videos

- Important collection

- Important collection

The Jews Banished 47 Times in 1000 Years - Why?

Zionist

strategies

- Plotting invasions, formenting civil wars, interreligious strife,

stoking racial hatreds and race war

The International Jew

By Henry Ford

Pravda interviews Ahmed Rami

Shahak's

"Jewish History,

Jewish Religion"

The Jewish plan to destroy the Arab countries

- From the World Zionist Organization

Judaism and Zionism inseparable

Revealing photos of the Jews

Horrors of ISIS Created by Zionist Supremacy

- By David Duke

Racist Jewish Fundamentalism

The Freedom Fighters:

Hezbollah

- Lebanon

Hezbollah

- Lebanon

Nation of Islam

- U.S.A.

Nation of Islam

- U.S.A.

Jewish Influence in America

- Government, Media, Finance...

"Jews" from

Khazaria stealing the land of Palestine

The U.S. cost of supporting Israel

Turkey, Ataturk and

the Jews

The truth about the Talmud

Israel and the Ongoing Holocaust in Congo

Jews DO control the media -

a Jew brags!

- Revealing Jewish article

Abbas - The Traitor

Protocols of Zion

- The whole book!

Encyclopedia of the

Palestine Problem

The

"Holocaust" - 120 Questions and Answers

Quotes

- On Jewish Power / Zionism

Caricatures / Cartoons

Activism!

- Join the Fight!