Jewish Center on Jewish propaganda in Japan and the efforts to mobilize Japanese Christians for the Jewish cause

The Jewish Israeli-based Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs has published a report entitled "The Jews of Japan" by two of its researchers, the Jews Daniel Ari Kapner and professor Stephen Levine. The document is found in the Center´s "Jerusalem Letter", No. 425, dated 1 March 2000. Most of its contents is the usual intra-Jewish stuff, but there are som interesting points on for instance the influence of Jewish holocaust propaganda in Japan, trying to brainwash the citizens of this Asian nation - just as they successfully have done in the West.

There are also some interesting points on pro-Zionist Christians groups in Japan. The latter are a big joke as the very holy scriptures of the Jews show nothing but total contempt of everything Christian, and especially the "Jewish heretic" Jesus Christ. In Israel, Jews have a habit of regularly spitting on Christians, but in far-away Japan these "useful idiots" - Shabbos Goyim - in the Christian sphere lend their services to the Jewish state.

Here follows excerpts from the report, omitted passages are marked with [...].

No one - apart perhaps from a few Japanese who see themselves as descendants of one of the lost tribes of Israel - would think of Japan as in any sense a Jewish homeland. Yet among the many shrines and temples, Shinto and Buddhist, there stand occasional monuments to Jewish commitment and endeavor. As ever, this is part of a heritage in which hope and despair, longing and sacrifice, war and struggle, have all been mingled together.Certainly this is true of Tokyo, whose Jewish community rose improbably out of the ashes of Allied victory. Probably there were more Jews in Japan during the postwar American Occupation than at any other time in the country's long history. Although the Occupation ended in 1952, an American military presence persists, with armed forces based in Okinawa as well as at other facilities. As a result, American Jews, both men and women, remain in Japan, able to take part in Jewish life if they wish to do so. At Yokosuka naval base near Tokyo, for instance, there is a small "chapel," complete with Torah scroll, which is used on the High Holy Days and on other occasions. It would not be surprising if on these days the number of Jews worshiping at American military facilities were comparable to the numbers taking part in services at Japan's two synagogues, in the capital, Tokyo, and in western Japan (Kansai) in the port city of Kobe.

[...]

The Tokyo community - now Japan's largest - was slower to develop. Indeed, the Japanese capital only became an important center of Jewish life with the arrival of the American Jewish servicemen. From the postwar period through to the present, small numbers of Jews regularly arrive from the United States and Western Europe for business, academic, or professional reasons. The Tokyo community has a higher profile than Kobe, and the presence of the Israeli Embassy in the capital also may give members some additional opportunities for cultural and social activities. The Jewish Community of Japan, Tokyo's central representative body, is affiliated with the World Jewish Congress.

[...]

Some services are conducted by visiting rabbis. In 1999, for example, a Chabad rabbi visited the Kobe community during Passover before returning with his family to his position in Hong Kong. Over the High Holy Day period the community was assisted in 1999 by a very popular Israeli, who led services which attracted many other Israelis from their work in Osaka and elsewhere.

[...]

For instance, during 1917-20, in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Jews of Yokohama and Kobe were able to offer significant help to several thousand Jewish refugees with the cooperation of the Japanese government. Many of these refugees had been unable to land in Japan because they lacked the necessary funds. This problem was resolved through the help of Jacob Schiff, the leader of the New York banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb, and Company, and the then president of the American Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS). Since Schiff had given Japan important financial assistance during the Russo-Japanese War, his request to make Yokohama and Kobe transit centers for the refugees was quickly accepted.

[...]

Some Japanese see parallels between their own personal and family wartime tragedies and those experienced by the Jews of Europe. Anne Frank's Diary of a Young Girl has been required reading for Japanese students for many years, and copies of the book can be seen in many Japanese homes. The book first appeared in Japan in 1952 and has since sold millions of copies. There have been numerous student essay contests about the work and there is even a company named after her, Anne Co., Ltd.

Films about the Holocaust are frequently shown in Japan, both on television and in the movies. The most recent to gain wide exposure is the award-winning Italian movie "Life is Beautiful." Other incidents and events (such as the trials of Nazi war criminals) have also brought the Holocaust to Japanese public awareness. There is a Holocaust Museum in Hiroshima and a Holocaust Resource Center in Tokyo, as well as some Japanese poetry comparing Hiroshima with Auschwitz.

[...]

Most Japanese people lack any awareness of Jews, which in some cases seems in many ways quite remarkable.

[...]

Publications identifying the Jews as the reason for Japan's problems have had their run, but seem in the end to have had only a shallow influence on policies or events. Nevertheless, ignorance does leave scope for considerable embarrassment. In October 1999, a Japanese publication, The Weekly Post, which has 852,000 subscribers and describes itself as the best-selling news magazine in the country, focusing on politics and the economy, published a story on the proposed acquisition of a Japanese bank, and soon generated strong complaints by Jewish groups, particularly outside of Japan. The Weekly Post quickly retracted the article and carried an apology on its home page. The publication explained its error by noting that "the problem stemmed from the stereotyped image of the Jewish people that many Japanese people have."

On occasion, Japanese images of Jews - to the extent that they have any - display a certain ambivalence. If some Japanese view Jews as powerful or affluent, others admire Jewish intellect and prosperity. Some have argued that Japan should learn from what is imagined to be Jewish business tactics and strategies. More typically, Japanese rarely meet Jews or, more accurately, realize that they are doing so. In this sense, Jewish people are seldom if ever distinguished from other foreigners unless they take some action themselves (such as observing dietary laws, the Sabbath, or holidays).

[...]

Japanese businesses were largely willing to comply with the Arab boycott and it was not until the 1990s peace process gained momentum that Japanese companies began to take a more active role in the Israeli economy. In addition, there are some Japanese university staff who conduct research into the Hebrew language and Jewish affairs. In 1995, the Japanese-Jewish Friendship and Study Society was established, and the fourth volume of the group's journal, Namal, was published in 1999.

Japanese Fascination with Judaism and Israel

As in other countries, some Japanese have been fascinated with kibbutz ideology, going to work for a time as volunteers at kibbutzim. It is likely that - apart from idealism and a sense of adventure - the collective approach of kibbutz life resonates well with Japanese values, which traditionally give primacy to the group over the individual. In 1963, Tezuka Nobuyoshi set up the Japan Kibbutz Association (Nihon Kibutsu Kyokai) which grew to 30,000 members within a few years. This group produced a number of publications and sent Japanese to volunteer on kibbutzim in Israel. One Japanese person who volunteered in Israel with the association wrote the 1965 best-seller, Shalom Israel, describing the warmth of kibbutz life.

Another group which sends Japanese to volunteer on kibbutzim is the Makuya, a pro-Israel Christian group which claims to have 60,000 members. The group was founded by Teshima Ikuro, who believed that the Japanese originate from one of the ten lost tribes of Israel. Some of the Makuya's pro-Israel activity included a rally in front of the United Nations headquarters in New York in 1971. After Japanese terrorists opened fire in the Tel Aviv airport in 1972, Teshima went to Israel to apologize to the families and offer bereavement. As well, 3,000 members led the first demonstration in Japan, held in Tokyo after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, to promote peace in Israel.

Another pro-Israel group is the Japanese Christian Friends of Israel, with perhaps 10,000 members. Its headquarters, Beit Shalom (House of Peace), is located in Kyoto. The group is also well known for its choir, the Shinome (Dawn) Chorus, which sings Israeli and Japanese songs and has traveled to Israel, Europe, and the United States. The group's main ideology centers on support for Israel and includes prayers for the coming of the Messiah. Rather than encourage conversion to Christianity, the group emphasizes peace between peoples. The Mayor of Jerusalem, Ehud Olmert, visited Beit Shalom in 1999. Jews and Israelis are specifically welcome to stay at Beit Shalom for up to three nights free of charge.

Kampo Harada, one of Japan's most famous calligraphers, also believed that the Japanese were descended from the lost tribes. Kampo went all over the world to do calligraphy, even traveling to Israel to paint for Yitzhak Rabin. Kampo was an earnest collector of Judaica. Hidden in the back of his Kyoto museum is a small room filled with Jewish books, three Torah scrolls, and various Jewish objects for use with prayer. Kampo's impressive collection includes hundreds of books about Israel, Jewish thought, prayer books, and books in Hebrew. There are rare works such as the Babylonian Talmud, the complete Zohar, and a Torah scroll which was saved at the end of World War II by an American soldier in Germany. Kampo collected Jewish books for forty years, and has another 4,600 books being held at a museum in Shiga-ken.

[...]

The Japanese and the Jews - the subject of more than one book - do share much in common, as complex peoples who are among the world's most enduring and most modern, at once traditional and innovative, respectful of the past yet zealous for the future. If any bridge is needed between them, it is surely in the example of a Japanese diplomat - long neglected both by Japanese and by Jews - a man who, nearly 60 years ago, held life in his fingertips, in the form of pieces of paper, and gave them to all that he could reach - Sugihara, a righteous Japanese who helps make it possible for Jews to visit and live in Japan in warmth and with pride.

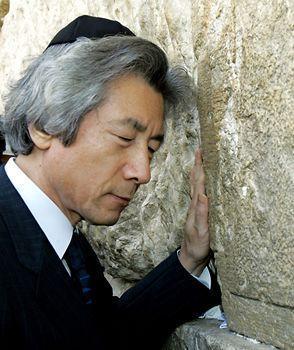

Koizumi in Israel

|

Races? Only one Human race United We Stand, Divided We Fall |

|

No time to waste. Act now! Tomorrow it will be too late |

|